After an incredibly relaxing day in Rumi and Andrea’s flat — interestingly labeled “el-Faradaws,” the word for Paradise — I decided by Day 2 in Cairo that it was time to get out.

The goal was to walk down south from Bab Zwayla, the southern gates of the 11th century Fatimid city, through the quarter known as Darb al-A7mar, or “the Red Road.”

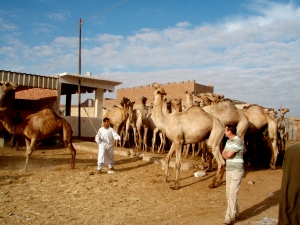

By now you know I’m a sucker for nostalgia, and here’s one of the many reasons I love Cairo: the city is still marked and known by these same elements of nostalgia. Going to the camel market? Good luck: nine-tenths of all cab drivers will bring you to Shaar3a sou5 al-gamal, on the way to Imbaba, where the camel market has been for centuries (and before the present government relocated it to the tiny village of Birqash some time ago) or Shaar3a Sudani, where camels were driven up from the south from the Sudan. Much of the city is marked in very much the same manner, and the names alone are rather evocative, even if the markets have changed: the area between the complexes of al-Azhar and al-Ghuriyya (called Butneya), is pocketed with what are still called “stitches” (ghorza in Arabic), tiny blind pockets where hashish was smoked and illegal business transacted. Nowadays, it’s where the men retreat for their sheeshas.

The word darb is actually a pretty neat one, I think, and I always get excited when I see it on a street sign. There are a couple names for roads in Arabic, and all of them have specific connotations, the most commonplace one being the word for street, shaar3a, (which incidentally, linguists, carries the same root as the word for Islamic law, shar3ia). Darb, however, is a path cut specifically across desert — a camel road — and you almost exclusively hear it out in the desert when locals are describing unpaved paths that connect oasis towns with one another. The Darb al-A7mar was one such road, leading from the southern gates of the old Fatimid city past the southern City of the Dead to join up with trade routes to the south. Though not entirely devoid of tourists, the quarter is enough of a network of labyrinthine alleyways and medieval staircases that you usually lose the aganib with the cameras and big hats sometime around Bab Zwayla.

It’s been blazing hot in Cairo, and yesterday was dusty in particular. I caught a cab to the Ghuriyya complex, which has a stunning, high covered entrance and is about a couple hundred yards before al-Azhar. Most of the complex is original and currently rented out to local artists as studios (but God: it’s hot in there). Ghuriyya lies in the exact center of Shaar3a al Muizz,one of the central points of interest in downtown Cairo. Most of the really spectacular stuff is more towards the Coppersmiths’ Bazaar (see what I mean about names? How evocative is that!). It runs about half a mile from the Northern Gates (or the “Open Gate”) near the mosque of al-Hakim (more on him later) and continues until the Tentmakers’ Market.

Entrance to the Ghuriyya caravanseri and palace: formerly, the whole street behind was covered and was the haunt of cloth merchants and thieves.

You turn left from Bab Zwayla onto Darb al-Ahmar, which has three names, depending on what part of the quarter you’re in: Tabbana Street, Bab al-Wazir, and the so-named Darb.

I’ve come to regard mosque-hopping as something of a hobby — back in the States, I’d stop into Catholic churches on long drives just to get out and stretch and have myself a little prayer, look at the statues. I kind of find mosques a nice place to relax: invariably, they are beautiful, cozy, and no one really bothers you if you look like you’re just there to take a load off.

Naps, therefore, are a big thing on such excursions. Because everyone takes off their shoes, the carpets are prime targets for a snooze, and most of the locals oblige themselves in the afternoon.

I also like mosques in particular for their facilities: in contrast to most lavatories in Cairo, bathrooms are at a premium in Islamic Cairo, at least for men. Not only can you find yourself a clean toilet, but practically take a bath for free due to the ablutions fountains everywhere. And truth be told, there’s something to the practice of wudu5, which is incredibly refreshing after a jaunt through the dustiest of quarters.

“Have you prayed the 3asr?”

No, sorry, I’m not Muslim.

Ah! You are American?

I said I wasn’t Muslim. Not that I didn’t speak Arabic.

This was how I met Gamal, who is the supervisor for three of the local mosques in Darb al-A7mar. Not only did he get me up into minarets, but the man opened the door to the still-being-renovated Qasr al-Azraq, the Blue Palace of Sultain Qait Bey.

I should also point out the remarkable amount of cruelty that goes down in the market. Camels are beaten with cane poles by their drovers to stay in their circles and keep them in line. When a camel is brought up for auction, its cheeks are hit with the same poles so it will growl and reveal its teeth. Some have blood in their eyes. Not for the faint of heart.

I should also point out the remarkable amount of cruelty that goes down in the market. Camels are beaten with cane poles by their drovers to stay in their circles and keep them in line. When a camel is brought up for auction, its cheeks are hit with the same poles so it will growl and reveal its teeth. Some have blood in their eyes. Not for the faint of heart.

Little did I know. Tantawi, known for his rather liberal attitude, reportedly gave a niqabi a metaphorical lashing when she repeatedly refused to remove the veil; he kept insisting (to his right) that he knew “more than the people that gave birth to her,” and that the niqab was NOT a part of Islam. When she finally took it off, Tantawi is reported to have said, “And you look like this? What would you have done if you were even a little bit pretty?” (In theory, the niqab guards men against the temptation of a beautiful woman’s face — basically, Tantawi was shutting her self-image down)

Little did I know. Tantawi, known for his rather liberal attitude, reportedly gave a niqabi a metaphorical lashing when she repeatedly refused to remove the veil; he kept insisting (to his right) that he knew “more than the people that gave birth to her,” and that the niqab was NOT a part of Islam. When she finally took it off, Tantawi is reported to have said, “And you look like this? What would you have done if you were even a little bit pretty?” (In theory, the niqab guards men against the temptation of a beautiful woman’s face — basically, Tantawi was shutting her self-image down)